In Pursuit of Things Past is a small but significant showing of work by the artist and author, Darren Coffield. The show includes four new works from the Interspatial Paintings (jigsaw) series and four early works from 1997.

The artist first began experimenting with jigsaws in 1989, using his own photographs made into jigsaws with the pieces rearranged. The critic David Sylvester was a collector, and they were subsequently exhibited at Benjamin Rhodes Gallery in 1992, Better Than Domestic Shit curated by Joshua Compston. Coffield abandoned the format in 1993 and did not revisit it until 2011 as something to do while looking after his first-born child.

Indeed, Coffield’s still lifes may draw on Chardin, but the lineage is direct to Cezanne and Braque

In 2015, he took the series one step further by using the die-cut board as a direct painting surface for portraiture and still life. It’s mainly been the small-scale portraits we’ve seen, notably at the 2016 exhibition Francis Bacon/ Darren Coffield at Herrick Gallery, and the series has produced two small masterpieces – Self-Portrait, (Piano Nobile, 2015) and the Fantin-Latour-like Tea Time, (Herrick Gallery, Spectrum, 2016). The Bacon/Coffield show allowed us to simultaneously examine the reordering of the figure, particularly the face, in the work of both artists. In the work of the latter, it is the reordering of the die-cut pieces which is the vehicle for achieving this.

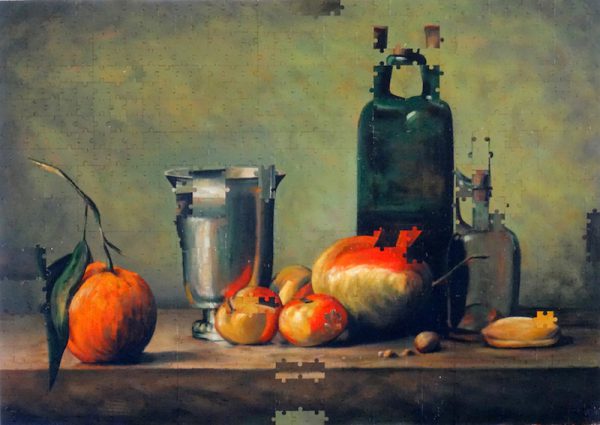

For the first time, Dellasposa Fine Art is displaying four much larger and technically ambitious works and their outing has been much anticipated. Coffield uses as his subject four 18th century still lifes by Chardin. There’s a playful mystery in the way these works are created. To begin with, there’s Coffield’s innate technical mastery: the brushwork is sensual, fluid and precise, absolutely holding that tension required for the die-cut paintings to work across the span of the picture surface. The teasing logic of where the displaced ‘pieces’ belong is something you can never quite work out. For all the visual disruptions, the work ultimately speaks of the lusciousness and physicality of painting. Yet such disruptions simultaneously hold us back from total indulgence and prevent the work from becoming ‘museum pieces’, although it’s a characteristically dangerous game Coffield plays.

Darren Coffield Dead Game II (After Chardin) 2015

As for the four early works – executed when the artist was 27 years old, any opportunity to see the early work of any serious artist is fascinating, and these works are jewel-like – luminescing as they do like icons in the crypt-like basement of Dellasposa. Once again, Coffield is in dialogue with the canon, and this is, without doubt, the central theme of the show. Significantly, we have an homage to two works by Velàzquez from the Wallace Collection: Melancholia of the Obscure Historical Figure (after Prince Baltasar Carlos in Silver) and Lady With A Fan. The boy prince figure is similar to both Las Meninas and Infanta Margarita Teresa in a Blue Dress, both of which Picasso painted versions – in the case of Las Meninas, a total of 58 times in 1957. The other master of theme and variation in the work of Velàzquez was Francis Bacon who painted versions of Portrait of Innocent X at least 45 times over a much greater time span, but whose early versions certainly predate Picasso’s epic series by 7 years.

So the fact that Coffield made these two paintings in 1997 after Velàzquez, certainly tells us something about the young artist – coincidentally about the same time as another contemporary master of the brush, Glenn Brown, was turning his attention to Rembrandt. While Bacon chose as his great theme the screaming popes, Coffield found a much tenderer religious subject for his early painting series in the form of madonna and child, a genre at its height in the latter part of the 15th century. The show features two of these works, based on Bellini’s Madonna del Prato and Lorenzo di Credi’s Madonna del Latte, which depicts the Madonna breastfeeding the infant. In all these early paintings, the faces are pixelated.

These works are tender, fragile. One of the most beautiful features of 15th century Italian religious paintings are the landscapes, so subtle and luminescent, and Coffield seems to engage utterly with this aspect – what’s enthralling is the questioning and dissemination of the painted background, the ground, the painting surface and the boundary of the painting, upon all of which the main image sits. Coffield’s treatment of these various layers has the effect of prising them apart in such a way as light is held captive within the surface of the painting. Skies pierce effortlessly through a foliage of brushwork in the madonna paintings; light is caged behind a perforated screen of black in the Velàzquez works.

As with the use of the dye-cut board, Coffield is experimental in his use of the painting surface, electing to paint on silk. Subsequent to the careful application of the main image, there’s a riot of brushwork applied to the reverse of the painting which is both subtle and moderately violent in its brusqueness and vulgarity of colour, and which, much like the reorganised jigsaw pieces, prevents the painting from settling into historical sentimentality. This hidden layer of painting gently pierces the delicate weave of the painted silk, pushing through those tenderly applied images of madonnas and divine infants, to produce a loose extruded pattern of dried bubbles of saturated paint.

Darren Coffield Encrypted Still Life II (After Chardin) 2016

This disruption of the surface creates the effect of a vigorously coloured scattered rain across the entire painting, and is a chromatic precursor to Coffield’s monochromatic Black Rain series, in that the mark making is concerned with holding that tension evenly across the painted surface. There’s an aesthetic dialogue with the background of Bacon’s screaming pope paintings, which although overt in their brutality, similarly, explore these qualities of surface tension and light held captive between layers of paint and raw permeable painting surfaces.

On first glance, the domestic tenderness of the subject matter is deceptive – for in fact all of these eight works contain small acts of sensual violence which take place on a kind of playing field where there is the constantly controlling tension of technique over the subject matter. In the early works, this tender violent tension is subtle but exists in a raw state; in the recent works these qualities are harnessed and finessed, but ever present: the face of the child, madonna and her suckled breast are first painted then pixellated, the painted face of a dead partridge is mercilessly rearranged, cadmium reds burn forth against a sea of olive ground in the still lifes far more searingly than they do in the Chardin originals.

Such distortions and violations are also aspects of the digital age – as referenced by the pixelation in the early work; in one of the titles, Encrypted Still Life (After Chardin); and in an excellent essayette by Coffield, Notes Towards Painting in the Digital Age, in the exhibition catalogue. The artist positions his work ‘face on’ in relation to modern life constantly interrupted by digital intervention, ‘detached’ in relation to the work of contemporary art, institutions, the marketplace and ‘aligned’ in relation to the non-commercial values of the early modernists as evidenced by their pioneering work in the solitary and contemplative genre of still life.

Indeed, Coffield’s still lifes may draw on Chardin, but the lineage is direct to Cezanne and Braque. These extraordinary new paintings are a seamless continuation of firstly those arists’ investigations of representation in relation to the two-dimensional painting surface, perception and knowledge, and secondly continued investigations into technical innovation within the centuries old tradition of the painted surface, of which Braque was an undoubted master. The way the sides of the bottle neck are split in two and swapped over in Encrypted Still Life II (After Chardin), is the perfectly overt demonstration of this.

Yet for all the history and engagement with the canon that these remarkable works contain (as alluded to by the show’s title), the subject matter and meanings are all drawn forward into the contemporary language of the artist and exist in the present and in the moment of the painting. Darren Coffield’s paintings never fail to live in the ‘now’ and his own language. Coffield is an artist at the top of his game: although the intimacy of Dellasposa serves well for an intimate encounter with these recent works full of grandeur and poise, and the gallery is to be applauded for showing them, they now deserve to be found a home within a permanent collection.

In Pursuit of Things Past also features work by Isabella Watling.

The exhibition is the subject of a curator’s talk by Jessica McBride of Dellasposa Fine Art this Wednesday 3rd May, 6 pm.

Words: Yseult Nash Top Photo: P C Robinson © Artlyst 2017 Aditional images © Darren Coffield all rights reserved