Darren Coffield’s well-presented Tales from the Colony Room, Soho’s Lost Bohemia, memorialises an epoch in the London world of the arts that now seems very far away, even though the once-famous Colony Room closed its doors as recently as December 2008.

Don’t Be Dull And Fucking Boring

– Muriel Belcher

Basically, the Colony Room was an insider space in the heart of the metropolis for people who in one way or another considered themselves to be outsiders. It was both inclusive, embracing both those who had money and those who didn’t, and also fiercely exclusive, rejecting those who didn’t fit. Its membership came quite largely but certainly not exclusively from the world of the visual arts, but actual artists were in a minority. It was extremely alcoholic but not especially friendly to drugs or drug-takers. It had links with the then London underworld, elements of which then flourished in Soho.

Colony Room, September 1, 1983. Left to right: Michael Wojas (barman and later successor to Ian Board), Tom Baker (Dr. Who), Mike Mackenzie (club pianist), Bacon, Bruce Bernard, unidentified woman, Thea Porter (dress designer, at Bacon’s feet), Ian Board (proprietor and for many years Muriel Belcher’s barman), Michael Clark, John Edwards, Tony Panter, Jeffrey Bernard (seated), John McEwen, and unidentified man © Neal Slavin

The founder of the Colony Room, which opened its doors in Dean Street in 1948, was a formidable Jewish lesbian (non-practising on both these counts, though she had a West Indian girlfriend) named Muriel Belcher. The most important founding member was the artist Francis Bacon, ‘adopted’ by Belcher, who called him ‘daughter’. In the early days of the club, Belcher paid him £10 a week to bring in friends, preferably those with money.

The Colony was one of the numerous drinking clubs in Soho, and it was on a small scale – one not-large room of the first floor. Its original function, under the then-existing licencing laws, was to bridge the gap in drinking hours between lunch-time and dinner. Pubs were forced to close at 2.30 p.m. It was founded at a time when male homosexual acts were illegal and fiercely prosecuted by the law courts. Many of its early members were gay, though it was never an exclusively gay operation. All sexualities were welcome, providing that they fitted the indefinable profile for membership. You belonged there, or you didn’t.

Given that I am now in my late 80s, I must be one of the few people in the London art world who remembers the Colony from close to its beginnings. Not that I ever joined – I was aware that I wouldn’t fit in and had no appetite for being insulted by the formidable Ms Belcher. Nevertheless, I existed on the fringes of that world. Notleys, the advertising agency in Hill Street where I worked as a copywriter from the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s, was closely connected with it. The artists Colquhoun and MacBride, founder members of the Colony, used to turn up regularly, just as we were closing our doors for the day. One of my fellow copyrighters was Oliver Bernard, brother of Jeffrey Bernard, who wrote the ‘Low Life’ column in The Spectator and who inspired the play Jeffrey Bernard Is Unwell, a smash hit in 1989. Jeffrey was a star at the club, and his brother, a poet, made no secret of how much he despised The Group, the weekly group of poets which I chaired and ran.

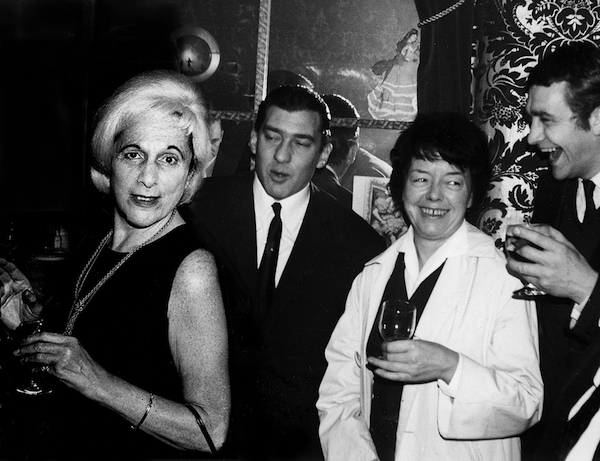

Colony Room founder Muriel Belcher with Ronnie Kray Photo David Marrion

The fascinating thing about the Colony now is how it existed as part of a London bohemian world, quite separate from the rest of British society. In this sense, it seems like an extension, or echo, of the world of French bohemia during the period following the Franco-Prussian War. Coffield’s book isn’t a straightforward narrative. It’s a highly skilful collage, snippets of evidence from many different narrators, some well-known, some pseudonymous, known only by the nicknames bestowed upon them at the club. Sometimes the witnesses agree with one another, quite often they don’t. Surveying the known names, one sees that most of them belong to people who are now dead. This is a vanished cultural world, entirely different from the one we seem to have today. It began to dissolve after the death of Muriel Belcher in 1979. It was never quite the same under Ian Broad, her immediate successor, who ran it from 1979 to 1994, and was rapidly becoming different under Michael Wojas, who ran it from 1994 until its closure in 2008 when the lease to its premises ran out. In Wojas’s day, it had a revival as a haunt for the YBA generation of artists and started doing exhibitions, which had never previously been a feature, though works by leading artists sometimes hung on its gloomy green walls.

Some notable points are these: first, the relative absence of women, though the list of notable members includes both Tracey Emin and Christine Keeler. Second, the almost complete lack of Americans, with the exception of R.B. Kitaj. There were American guests, but they never seem to have felt at home there. The Colony’s glory days were, however, exactly those who saw the rise to dominance of American art. There are interesting oddities as well. For example, evidence that Bacon, who claimed that he ‘didn’t draw’, could draw a perfect circle freehand. And Bacon’s claim that he was the predestined successor to Picasso. The answer to which is: ‘not quite’.

One thing that the book tends to point out is the absence today of a cohesive art world. What we have instead is a world in which big institutions like the Tate award brownie points: female, yes; non-Caucasian, yes; LGBTQ+, yes. Extra points for any combination of these characteristics. Visual originality welcomed but not necessarily required. We still have a taste for bad boys and bad girls, but on the whole, we prefer them to be safely dead.