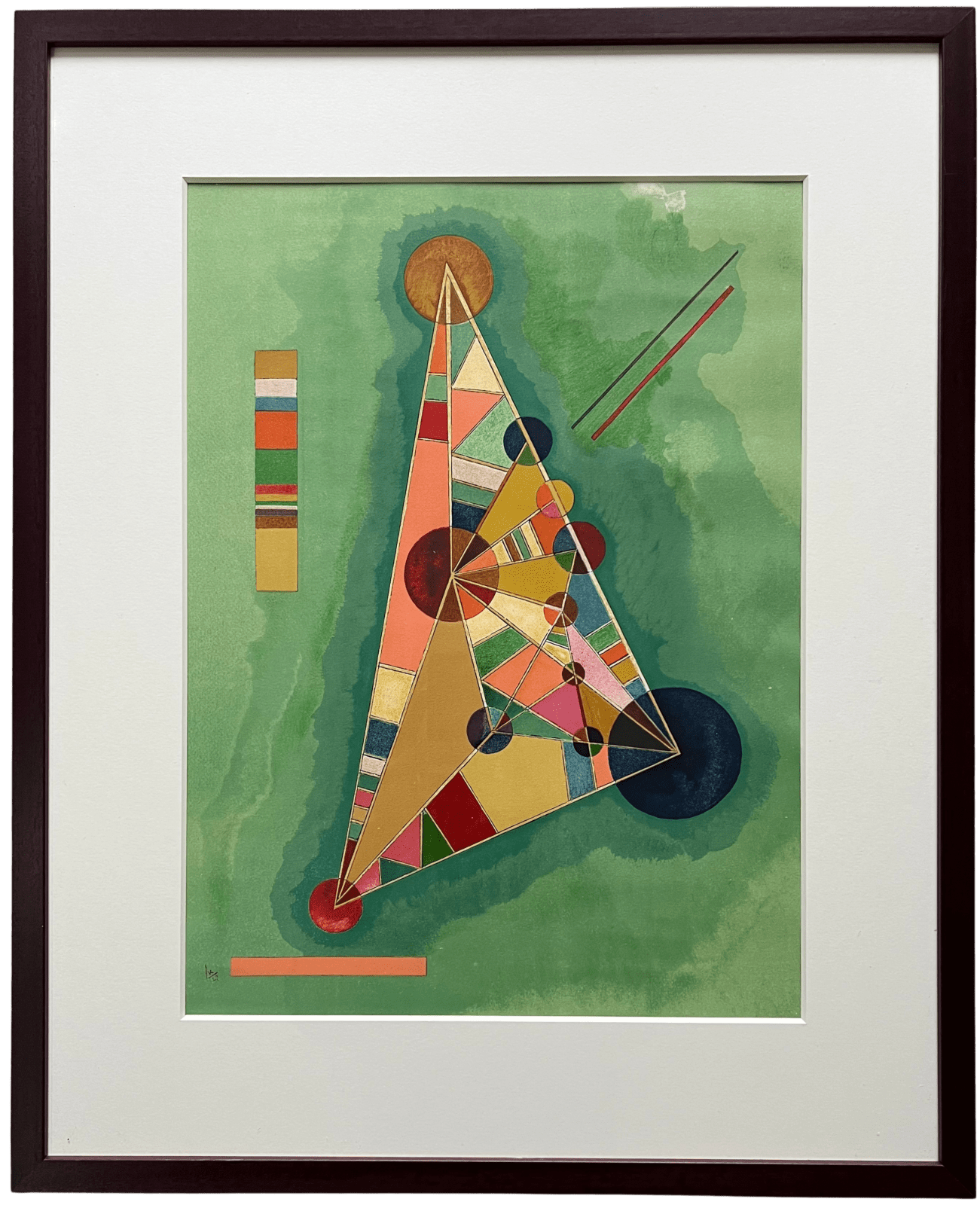

Wassily Kandinsky

Bunt im Dreieck, 1965

Lithograph in colours on Arches paper, framed

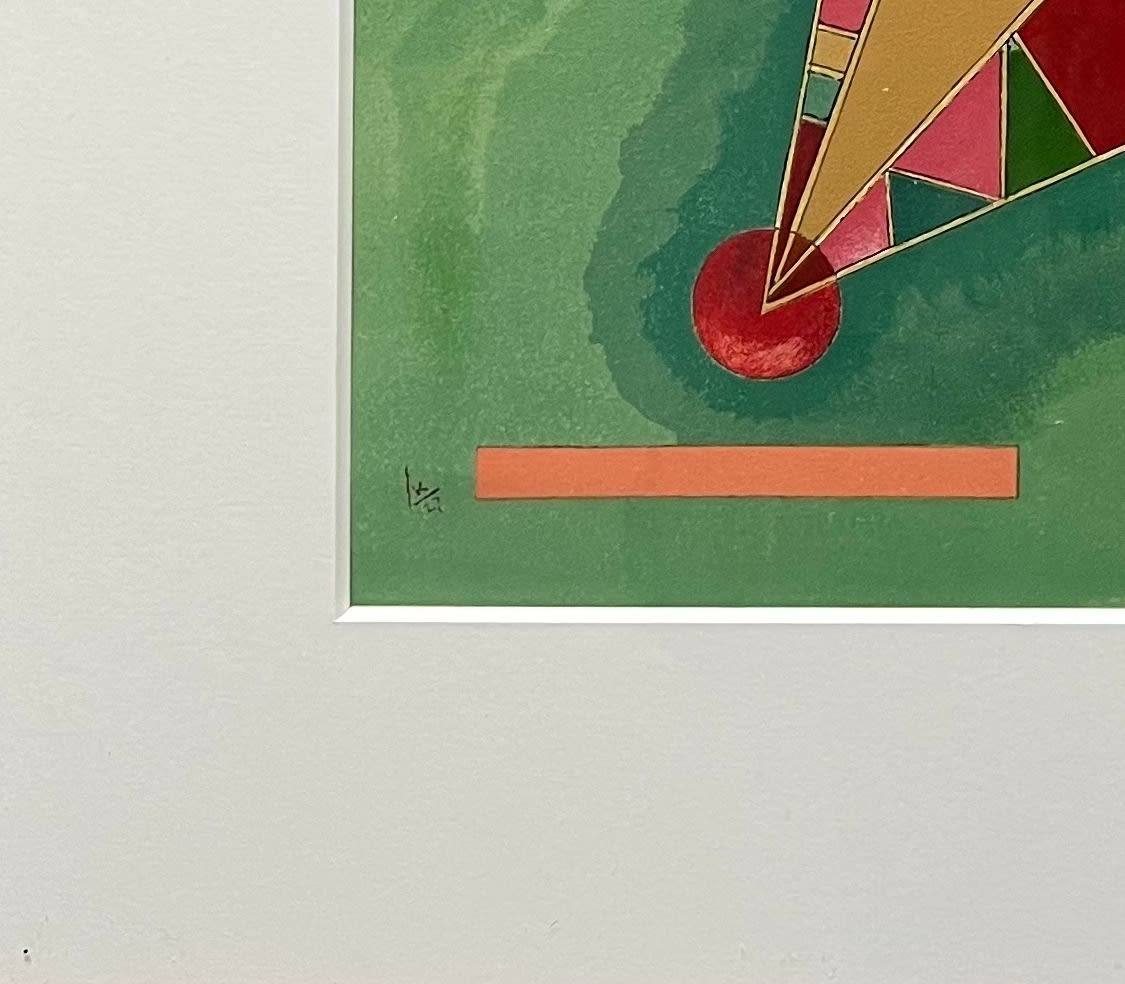

Signed in the plate, on recto

Signed in the plate, on recto

Sheet: 64 x 45.5 cm

Framed: 69.2 x 56 cm

Framed: 69.2 x 56 cm

© The Estate of Wassily Kandinsky

Weitere Abbildungen

'A triangle provokes a live emotion because it is itself a living being. It is the artist who kills it if he applies it mechanically, without inner direction.” Wassily Kandinsky,...

"A triangle provokes a live emotion because it is itself a living being. It is the artist who kills it if he applies it mechanically, without inner direction.”

Wassily Kandinsky, 1935

Bunt Im Dreieck (Variegation in the triangle) is one of the most remarkable examples of the philosophy that led Kandinsky to give spiritual value to geometric forms and colours during his Bauhaus years. Painted in 1927, this picture marks a decisive turning point in Kandinsky’s work. Due to rising inflation in Germany and the growing domination of the far right, who saw the Gropius school as a “dangerous home of Bolchevism”, the artist decided to leave Weimar for Dessau, following in the footsteps of many other Bauhaus professors and students. Distancing himself from artists who had embraced the rational precepts of Russian Constructivism or Supremataism, Kandinsky placed intuition and spirituality at the heart of his artistic approach. His painting, as Bunt Im Dreieck shows, was henceforth characterised by lyricism and a simplification of forms: immortalised shapes become calm and solemn and a magnificent range of colours once more nuances his pictures.

During these years the painter researched the interdependence of shapes and primary colours and the spiritual consequences of these relationships. He thus associates each shape with a colour (yellow with the triangle, red with the square and blue with the circle), integrating new elements in the psychology of forms, this principle having formed the basis of "Point and Line to Plane", published in 1926. In this text, the artist methodically elaborates a theory of abstraction in which primary geometric elements, the dot, the line and the plane, form relationships. All of the formal components of a work provoke different emotions in the viewer that the artist analyses in a near scientific manner. The colourful graphic style of Bunt Im Dreieck marvellously transcribes these elements: multiple coloured shapes unfurl from the centre of a majestic triangle levitating against a sea-green background painted with subtle shading.

The triangle occupies an important position at the core of this new visual vocabulary. As Kandinsky shows in his response to the “survey of the art of today” published by Cahiers d’art in 1935, in which he discusses abstract art and his choice of simple geometric shapes to express his impressions and emotions: “A triangle provokes a live emotion because it is itself a living being. It is the artist who kills it if he applies it mechanically, without inner direction. […] But like an “isolated” colour, an “isolated” triangle cannot by itself constitute a work of art. The same law of “contrasts” applies. One must not forget the power of the modest triangle. We know that, if we draw a triangle with very thin lines, on a white sheet of paper, the white inside the triangle and the white around it become very different, they receive different “colours” without us adding any colour. This is a physical and psychological fact. And, with the change of colour, it changes “its interior”. If you add another colour to this triangle, the sum of emotions increases in geometric proportion, this is not an addition but a multiplication.”

The lyricism and serenity that this composition evokes, as well as the use of simple geometric forms, recall certain works by Paul Klee. During their shared time at the Bauhaus school in Dessau, the two artists formed a strong friendship and sometimes produced pictorial inventions that were incredibly similar, as attested by Ruhende Schiffe (Resting Sailboats), executed in 1927. In this work we find the same freedom of tone, the same fresh colours and geometric shapes that characterise Bunt Im Dreieck. Aside from this stylistic similarity with his Bauhaus comrade, the softly fluorescent hues of the multi-coloured checkboard floating in Bunt Im Dreieck, together with its vibrant, atmospheric variations of tone, foreshadow the premises that would characterise Kandinsky’s Parisian period.

Wassily Kandinsky, 1935

Bunt Im Dreieck (Variegation in the triangle) is one of the most remarkable examples of the philosophy that led Kandinsky to give spiritual value to geometric forms and colours during his Bauhaus years. Painted in 1927, this picture marks a decisive turning point in Kandinsky’s work. Due to rising inflation in Germany and the growing domination of the far right, who saw the Gropius school as a “dangerous home of Bolchevism”, the artist decided to leave Weimar for Dessau, following in the footsteps of many other Bauhaus professors and students. Distancing himself from artists who had embraced the rational precepts of Russian Constructivism or Supremataism, Kandinsky placed intuition and spirituality at the heart of his artistic approach. His painting, as Bunt Im Dreieck shows, was henceforth characterised by lyricism and a simplification of forms: immortalised shapes become calm and solemn and a magnificent range of colours once more nuances his pictures.

During these years the painter researched the interdependence of shapes and primary colours and the spiritual consequences of these relationships. He thus associates each shape with a colour (yellow with the triangle, red with the square and blue with the circle), integrating new elements in the psychology of forms, this principle having formed the basis of "Point and Line to Plane", published in 1926. In this text, the artist methodically elaborates a theory of abstraction in which primary geometric elements, the dot, the line and the plane, form relationships. All of the formal components of a work provoke different emotions in the viewer that the artist analyses in a near scientific manner. The colourful graphic style of Bunt Im Dreieck marvellously transcribes these elements: multiple coloured shapes unfurl from the centre of a majestic triangle levitating against a sea-green background painted with subtle shading.

The triangle occupies an important position at the core of this new visual vocabulary. As Kandinsky shows in his response to the “survey of the art of today” published by Cahiers d’art in 1935, in which he discusses abstract art and his choice of simple geometric shapes to express his impressions and emotions: “A triangle provokes a live emotion because it is itself a living being. It is the artist who kills it if he applies it mechanically, without inner direction. […] But like an “isolated” colour, an “isolated” triangle cannot by itself constitute a work of art. The same law of “contrasts” applies. One must not forget the power of the modest triangle. We know that, if we draw a triangle with very thin lines, on a white sheet of paper, the white inside the triangle and the white around it become very different, they receive different “colours” without us adding any colour. This is a physical and psychological fact. And, with the change of colour, it changes “its interior”. If you add another colour to this triangle, the sum of emotions increases in geometric proportion, this is not an addition but a multiplication.”

The lyricism and serenity that this composition evokes, as well as the use of simple geometric forms, recall certain works by Paul Klee. During their shared time at the Bauhaus school in Dessau, the two artists formed a strong friendship and sometimes produced pictorial inventions that were incredibly similar, as attested by Ruhende Schiffe (Resting Sailboats), executed in 1927. In this work we find the same freedom of tone, the same fresh colours and geometric shapes that characterise Bunt Im Dreieck. Aside from this stylistic similarity with his Bauhaus comrade, the softly fluorescent hues of the multi-coloured checkboard floating in Bunt Im Dreieck, together with its vibrant, atmospheric variations of tone, foreshadow the premises that would characterise Kandinsky’s Parisian period.

Join our mailing list

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied to communicate with you in accordance with our Datenschutz. You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.