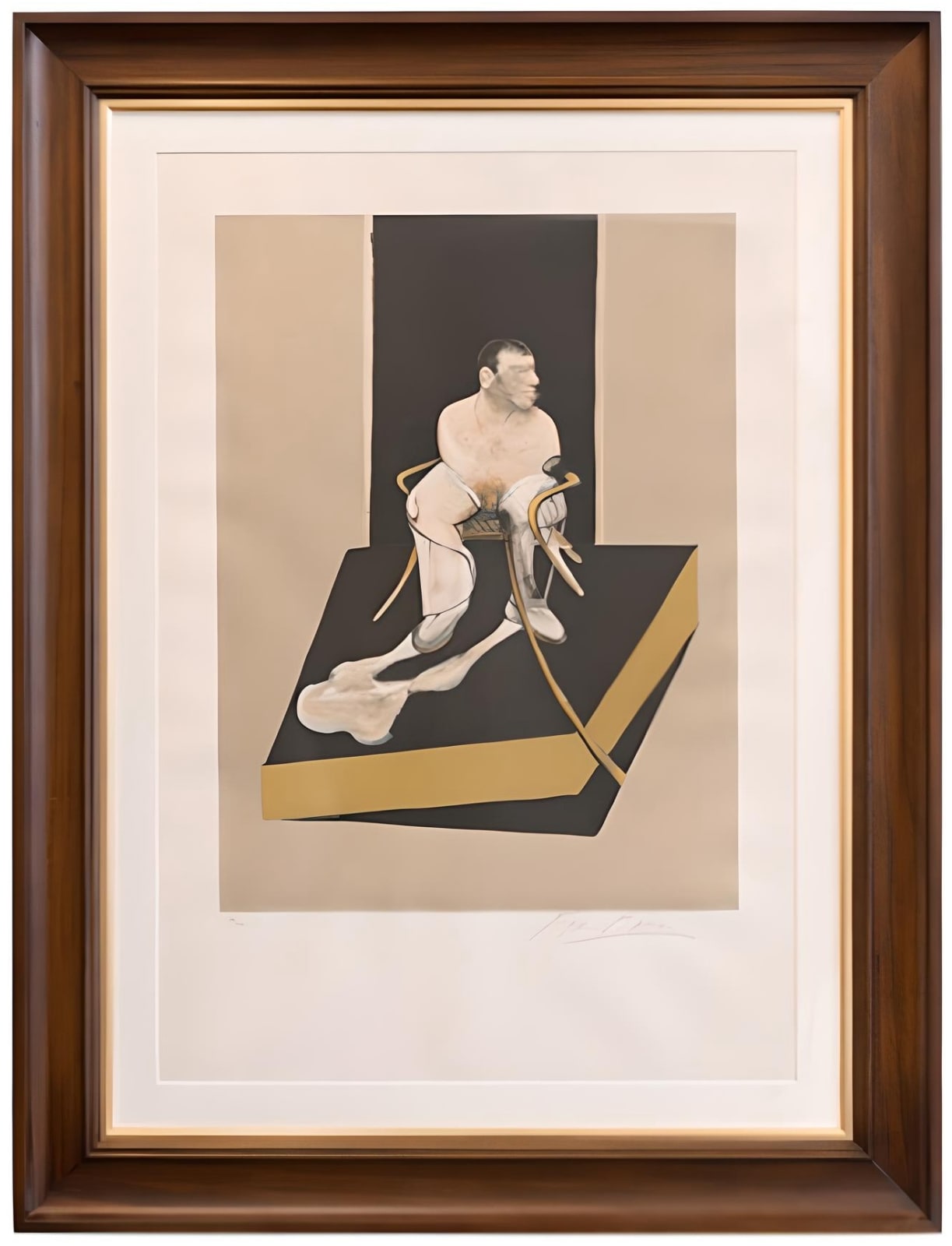

Francis Bacon British, 1909-1992

Triptych 1986-7 , 1987

Complete triptych composed of three etchings with aquatint in colour on Arches paper, with full margins, framed

Each panel signed by the artist in pencil, lower right on recto

Each panel signed by the artist in pencil, lower right on recto

Image: 65.2 x 48.6 cm; Sheet: 89.5 × 62.5 cm; Framed: 115 x 89 cm (each)

Triptych: 115 x 267 cm

Triptych: 115 x 267 cm

© Estate of Francis Bacon

Further images

When the Tate Gallery celebrated Francis Bacon (1909-1992) with a second retrospective in 1985, its director at the time, Sir Alan Bowness, declared him ‘the greatest living painter’. By then...

When the Tate Gallery celebrated Francis Bacon (1909-1992) with a second retrospective in 1985, its director at the time, Sir Alan Bowness, declared him ‘the greatest living painter’.

By then in his seventies, Bacon had been exploring the raw sensation of the human experience for more than 40 years. ‘I feel ever so strongly that an artist must be nourished by his passions and his despairs,’ he told art critic John Gruen in 1991. ‘These things alter an artist, whether for the good or the better or the worse.’

The following year, at the height of his fame, Bacon painted Triptych 1986-7, three monumental canvases that conflate public and private histories in his rarest and most celebrated format.

The suited figure in the left-hand panel is based on a press image of US President Woodrow Wilson leaving the Quai d’Orsay during the Treaty of Versailles negotiations in 1919. The right-hand panel is an over-scaled depiction of Leon Trotsky’s cloth-covered recording equipment, inspired by a photograph of his study taken soon after his assassination in Mexico City in August 1940. A single lamp illuminates the blood-stained sheet, a metaphor perhaps for the fleeting nature of life.

In the centre panel sits a figure resembling Bacon’s then-partner, John Edwards. His pose is reminiscent of the artist’s former lover, George Dyer, in the haunting eulogy Triptych August 1972, one of a series of ‘Black Triptychs’ that Bacon painted following Dyer’s suicide in 1971. With his naked body dissolving and his gaze fixed on the bloodied white sheet, he attempts to clasp the incongruous pair of cricket pads he is wearing, as if desperately trying to remain in the present.

The images, though half-connected by the strip of pavement, remain self-contained, the solitude of the figures heightened by the dark, canvas-like voids behind them.

As the 1950s progressed, Bacon’s own life began to infiltrate his work, with portraits of friends and lovers taking centre stage. Famously, however, he did not paint them from life, explaining that ‘even in the case of friends who will come and pose, I’ve had photographs taken for portraits because I very much prefer working from the photographs than from them’.

Working from secondary imagery also allowed him, he said, to engage with the impulses of the ‘nervous system’. In his ferocious contemplation of the human condition, he sought to reveal the raw animal spirit beneath, or what he called ‘the pulsations of a person’.

By the time he created Triptych 1986-7, Bacon had lived through almost the full gamut of the 20th century, experiencing personal triumph and turmoil in extreme measures. While basking in the extraordinary success of his Tate retrospective, he was still haunted by Dyer’s passing and had spent much of the previous decade in painterly confrontation with his own mortality. It is perhaps no coincidence that the source images in Triptych 1986-7 span nearly the entire length of Bacon’s life.

The historic implications of the iconography have come to resonate on many levels, too. The juxtaposition of Wilson and Trotsky has been interpreted by some as a recapitulation of Bacon’s intention to ‘paint the history of Europe in my lifetime’, and by others as an allusion to the American passport that was given to Trotsky in 1917, enabling him to travel from New York and re-enter Russia.

Then there’s the plinth on which Edwards sits. Propped open by an extended chair leg, it resembles a large reference book. Could this be what the Bacon scholar Martin Harrison calls the artist’s ‘sardonic review of the failings of a century’?

Bacon depicts the desk belonging to the assassinated Russian political figure, Trotsky. Murdered with an icepick in Mexico by a Spanish-born Soviet agent acting on Stalin's orders, Trotsky's body is draped in a bloodstained shroud. Although alluding to the violence of the act—eyewitnesses attested to Trotsky grappling with the assassin and even spitting in his face—the portrayal of the desk also alludes to the legacy of work that a great man leaves behind. When Bacon made this signed limited edition he was just five years before his own death, and clearly in contemplative mood.

By then in his seventies, Bacon had been exploring the raw sensation of the human experience for more than 40 years. ‘I feel ever so strongly that an artist must be nourished by his passions and his despairs,’ he told art critic John Gruen in 1991. ‘These things alter an artist, whether for the good or the better or the worse.’

The following year, at the height of his fame, Bacon painted Triptych 1986-7, three monumental canvases that conflate public and private histories in his rarest and most celebrated format.

The suited figure in the left-hand panel is based on a press image of US President Woodrow Wilson leaving the Quai d’Orsay during the Treaty of Versailles negotiations in 1919. The right-hand panel is an over-scaled depiction of Leon Trotsky’s cloth-covered recording equipment, inspired by a photograph of his study taken soon after his assassination in Mexico City in August 1940. A single lamp illuminates the blood-stained sheet, a metaphor perhaps for the fleeting nature of life.

In the centre panel sits a figure resembling Bacon’s then-partner, John Edwards. His pose is reminiscent of the artist’s former lover, George Dyer, in the haunting eulogy Triptych August 1972, one of a series of ‘Black Triptychs’ that Bacon painted following Dyer’s suicide in 1971. With his naked body dissolving and his gaze fixed on the bloodied white sheet, he attempts to clasp the incongruous pair of cricket pads he is wearing, as if desperately trying to remain in the present.

The images, though half-connected by the strip of pavement, remain self-contained, the solitude of the figures heightened by the dark, canvas-like voids behind them.

As the 1950s progressed, Bacon’s own life began to infiltrate his work, with portraits of friends and lovers taking centre stage. Famously, however, he did not paint them from life, explaining that ‘even in the case of friends who will come and pose, I’ve had photographs taken for portraits because I very much prefer working from the photographs than from them’.

Working from secondary imagery also allowed him, he said, to engage with the impulses of the ‘nervous system’. In his ferocious contemplation of the human condition, he sought to reveal the raw animal spirit beneath, or what he called ‘the pulsations of a person’.

By the time he created Triptych 1986-7, Bacon had lived through almost the full gamut of the 20th century, experiencing personal triumph and turmoil in extreme measures. While basking in the extraordinary success of his Tate retrospective, he was still haunted by Dyer’s passing and had spent much of the previous decade in painterly confrontation with his own mortality. It is perhaps no coincidence that the source images in Triptych 1986-7 span nearly the entire length of Bacon’s life.

The historic implications of the iconography have come to resonate on many levels, too. The juxtaposition of Wilson and Trotsky has been interpreted by some as a recapitulation of Bacon’s intention to ‘paint the history of Europe in my lifetime’, and by others as an allusion to the American passport that was given to Trotsky in 1917, enabling him to travel from New York and re-enter Russia.

Then there’s the plinth on which Edwards sits. Propped open by an extended chair leg, it resembles a large reference book. Could this be what the Bacon scholar Martin Harrison calls the artist’s ‘sardonic review of the failings of a century’?

Bacon depicts the desk belonging to the assassinated Russian political figure, Trotsky. Murdered with an icepick in Mexico by a Spanish-born Soviet agent acting on Stalin's orders, Trotsky's body is draped in a bloodstained shroud. Although alluding to the violence of the act—eyewitnesses attested to Trotsky grappling with the assassin and even spitting in his face—the portrayal of the desk also alludes to the legacy of work that a great man leaves behind. When Bacon made this signed limited edition he was just five years before his own death, and clearly in contemplative mood.

Provenance

Private CollectionLiterature

Francis Bacon: Estampes - collection Alexandre Tacou Number 22

Bruno Sabatier, Francis Bacon: The Graphic Work, no. 6

Miguel Orozco “The complete prints of Francois Bacon” 51, 52 & 53

1

of

18