-

Kunstwerken

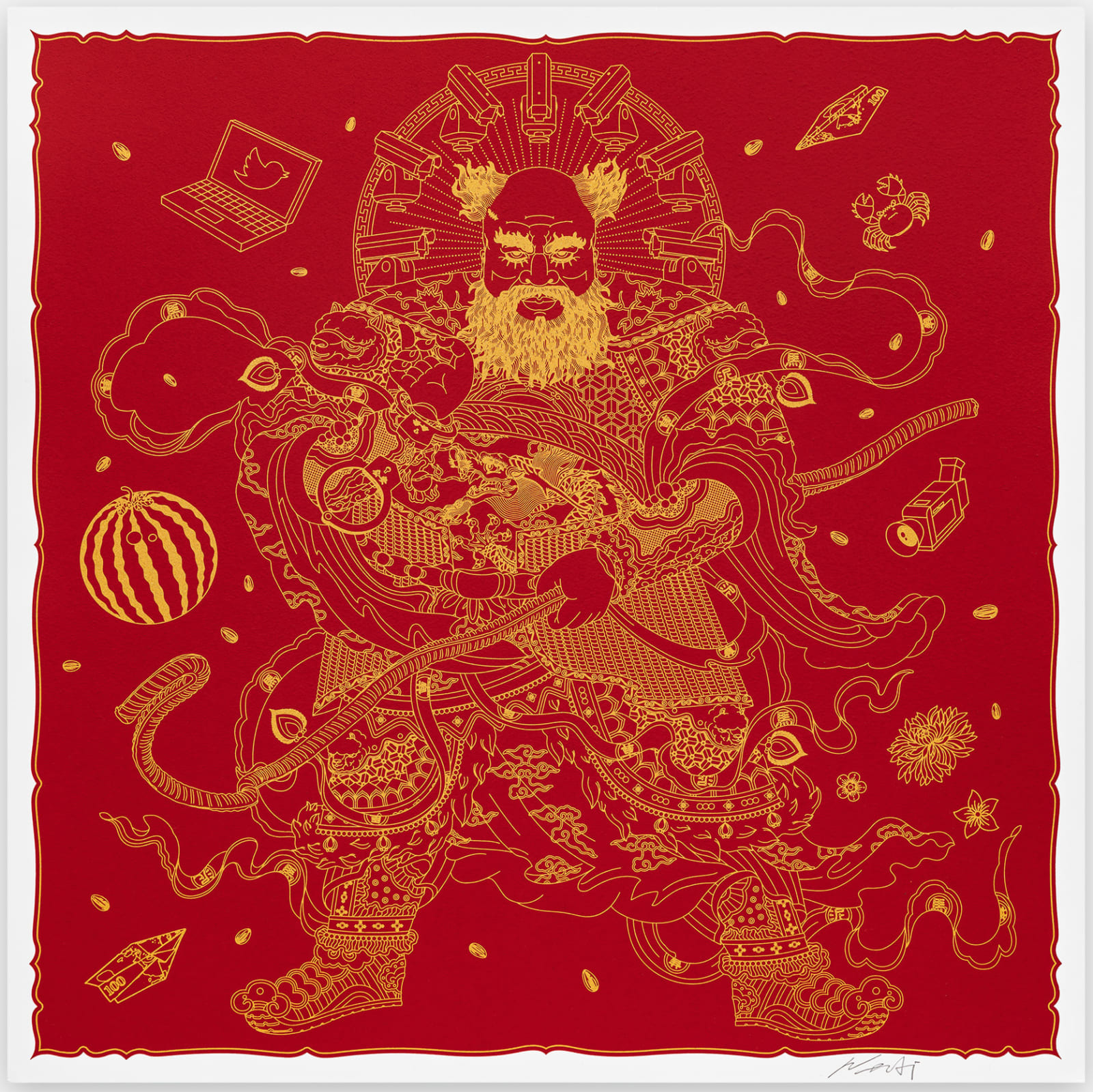

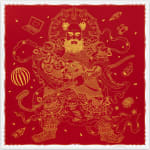

Ai Weiwei Chinese, 1957

Guardian, 2024Silkscreen composed of two colours with a metallic glitter base layer, on 410gsm Somerset Tub Sized Radiant White paper

Signed by the artist’s hand and numbered60 x 60 cm (23 5/8 x 23 5/8 in.)© Ai WeiweiFurther images

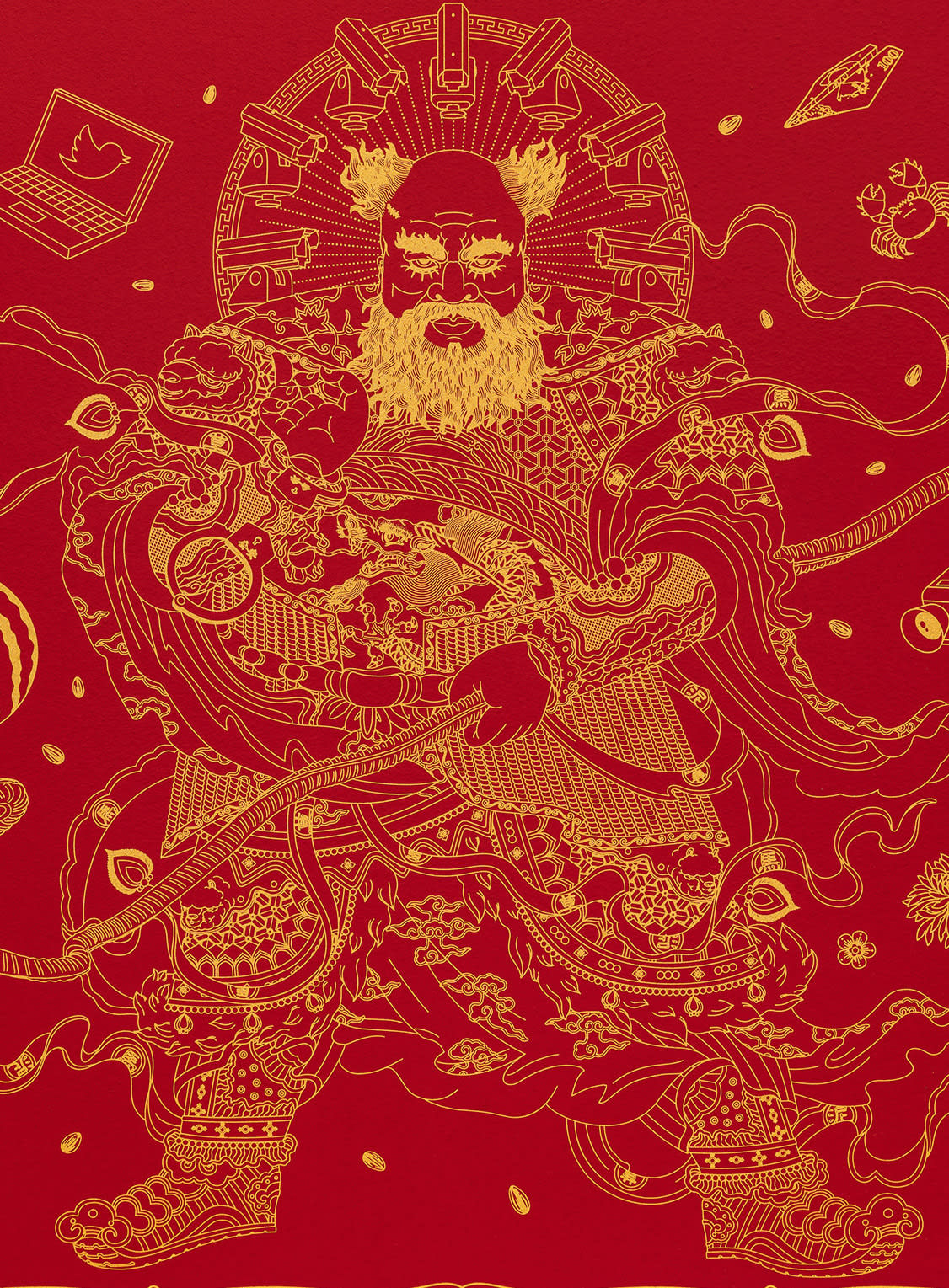

In this striking silkscreen print, rendered in luminous gold against a fortuitous red background, Ai Weiwei reimagines himself as a traditional Chinese Door God, a protective deity traditionally displayed during...In this striking silkscreen print, rendered in luminous gold against a fortuitous red background, Ai Weiwei reimagines himself as a traditional Chinese Door God, a protective deity traditionally displayed during Lunar New Year celebrations. The composition interweaves personal and political symbolism through an array of recurring motifs: surveillance cameras reference state monitoring, handcuffs recall his 81-day detention, and sunflower seeds and watermelons evoke memories of his exile in Xinjiang.

The artwork masterfully layers contemporary socio-political commentary with cultural heritage, as the artist positions himself as a guardian against forces of censorship, corruption, and surveillance.

Through this self-portraiture, Ai continues his tradition of merging classical Chinese imagery with contemporary critique, creating a powerful statement about resistance and protection in modern society.

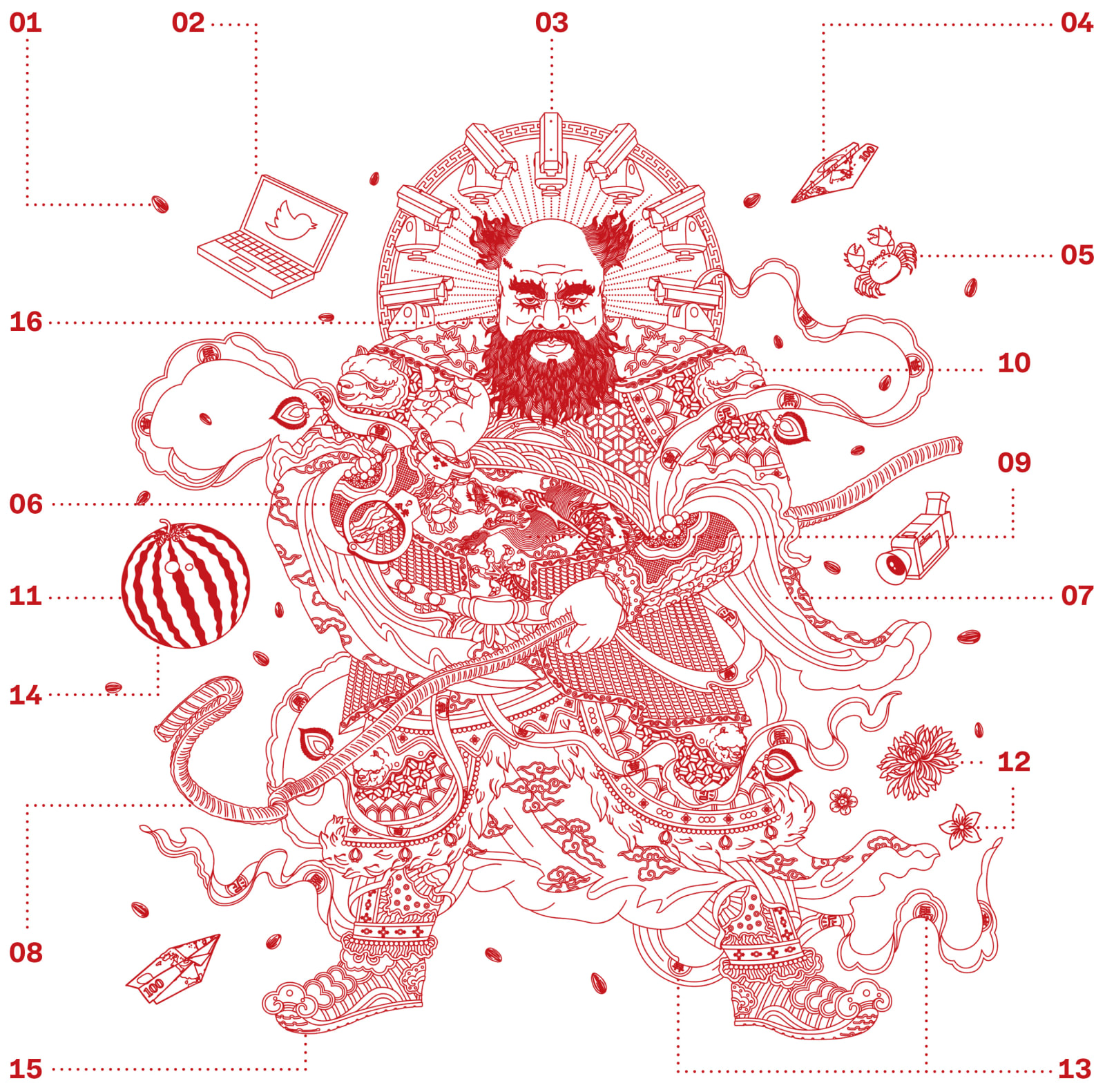

Symbolism:

01 · Sunflower seeds

Used in ceramic form by Weiwei for his famous installation, sunflower seeds were a common childhood snack and a nod to propaganda from the Cultural Revolution which cast Mao Dezong as the sun and his citizens as sunflowers.

02 · Twitter

This now-usurped logo nods to Weiwei’s use of the internet as a vessel for free speech. He joined the platform in 2009 when the Chinese government shut down his blog, and uses it vociferously to reflect on a wealth of subjects.

03 · Surveillance cameras

A literal representation of the scrutiny Weiwei has been subjected to throughout his life. When his former studio was encircled by state surveillance cameras, he decorated each of them with a traditional red lantern.

04 · Bank notes folded into paper planes

When Fake Cultural Development Ltd. was accused of tax evasion, the internet rushed to Weiwei’s aid. As well as transfers from around the world, bank notes folded into paper planes sailed over the walls of his studio compound.

05 · River crabs

A nod to the feast Weiwei hosted to mark the demolition of his studio in Shanghai. In Mandarin, river crab is a homophone for harmony – a government slogan coopted online for covert communication suffused with irony.

06 · Handcuffs

Referring specifically to his 81-day incarceration at the hands of the Chinese government, Weiwei uses handcuffs as a symbol of oppression and the denial of freedom.

07 · Traditional costume

Weiwei’s ensemble alludes to various deities from Chinese culture, drawing parallels between his artistic endeavours and their folkloric exploits.

08 · Rebar

Steel rebars, a construction material, refer to Weiwei’s investigation of corruption after an earthquake in Sichuan Province. He used reclaimed metal – warped by disaster – in a body of work dedicated to the catastrophe.

09 · Dragon

Weiwei uses the Chinese zodiac as a conduit to explore the dissemination of cultural heritage and the complex relationship of modern China with its own history. 2024 welcomes the year of the dragon.

10 · Caonima

Caonima or grass mud horse sounds similar to a popular profanity and emerged online as a way to circumvent the authoritarian control of language, which became more extreme during the Jasmine Revolution.

11 · Watermelon

Weiwei spent his formative years in exile with his father in Xinjiang Province. Melons grew well in the region’s sandy soil. In his work, they symbolise the generosity of nature and our ability to thrive under inhospitable conditions.

12 · Flowers

In 2013 Weiwei announced that he would place a bouquet of flowers in the basket of a bicycle outside his studio every day until his passport was returned. It took 600 days. For him, flowers represent freedom – intellectual and literal.

13 · Chinese characters

Since 2005, alongside making artwork, Weiwei’s primary focus has been writing. He observes that shifts in society are linked closely to shifts in language. By extension, he recognises the power of language to change the world.

14 · Red

In Chinese culture, the colour red is a symbol of fullness and good fortune. Historically it has also been associated with justice and, in the absence of justice, revolution.

Join our mailing list

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied to communicate with you in accordance with our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.