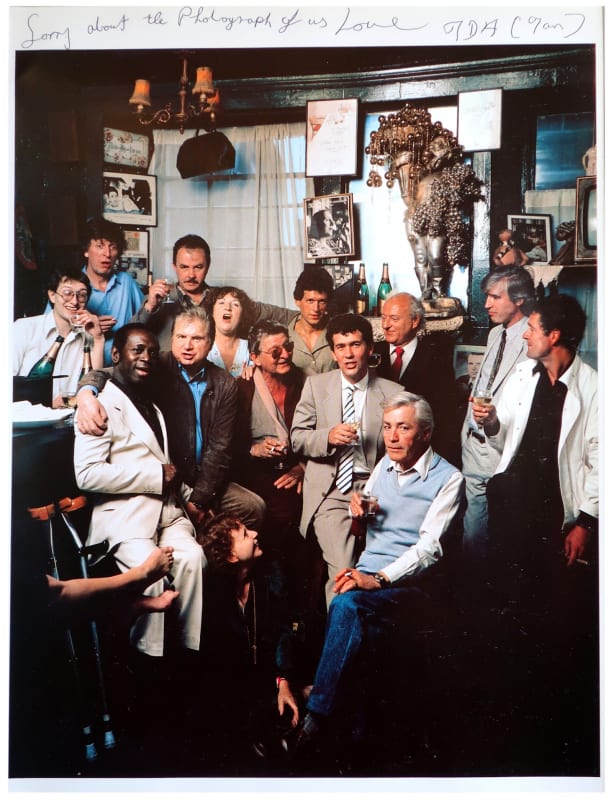

Before his death in 2018, Michael Peel recalled taking an American acquaintance to the Colony Room Club in London’s Soho. “His jaw hit the floor. There was Molly Parkin with her tits out […], Peter Langan in a dirty white suit lying on the floor kicking his legs in the air, and George Melly with a [trans] clarinettist jamming with Barney Bates. I said, ‘I told you, you don’t have clubs like that in California.’”

The computer salesman is one of dozens of posthumous and living contributors to Darren Coffield’s Tales from the Colony Room: Soho’s Lost Bohemia, an oral history of London’s most infamous private drinking club. Despite liquor license reforms, attempted shakedowns, and the national smoking ban, the bar ran continuously and riotously from 1948 to 2008. As explained by Barry Humphries in the book’s foreword, the Colony Room “provided an atmosphere of delectable depravity for [a] select company of alcoholics and would-be artists.”

For anyone other than their participants, scene memoirs rank among the most insufferable literary genres, bender chronicles more so. In the sober light of day and in print, most bar room anecdotes fail to make the leap from prurience to insight. Thankfully, Tales from the Colony Room is neither a rose-tinted take on libated genius, nor a prop of bar-fueled mythologizing. Coffield’s project transcends such myopic pitfalls, and triumphs as a rumination of the artistic exchanges, affections, cruelty, and regrets of the Colony’s members.

Until 1988, pubs were prohibited from serving alcohol between the hours of 3 and 6pm, an edict that propagated an entire industry of private drinking establishments. The Colony, located up a rickety staircase at 41 Dean Street, was little more than a single room with a raggedy booze-soaked carpet. Thirsty patrons appreciated its no-frills simplicity. “The Colony was not just a bar, but also an artistic support centre, psychiatrist’s couch, [and] local post office” Coffield explains. “The members came and behaved as a wayward family.”

Francis Bacon, undoubtedly the Colony’s most famous member, was affectionately dubbed “daughter” in recognition of his favor with the Club’s founder and proprietress, Muriel Belcher (“mother”). Other celebrated regulars included Cecily Brown, Lucian Freud, Peter O’Toole, John Hurt, and Lady Rose McLaren. Despite its renowned clientele, the Colony stood out for its relatively equalitarian ethos. “There was no clique, crowd, way to dress, or act, and no required station in life in order to be a member,” Coffield explains. “Lords, landowners, barrow boys, musicians, singers, strippers, stagehands, and petty crooks all drank there.”

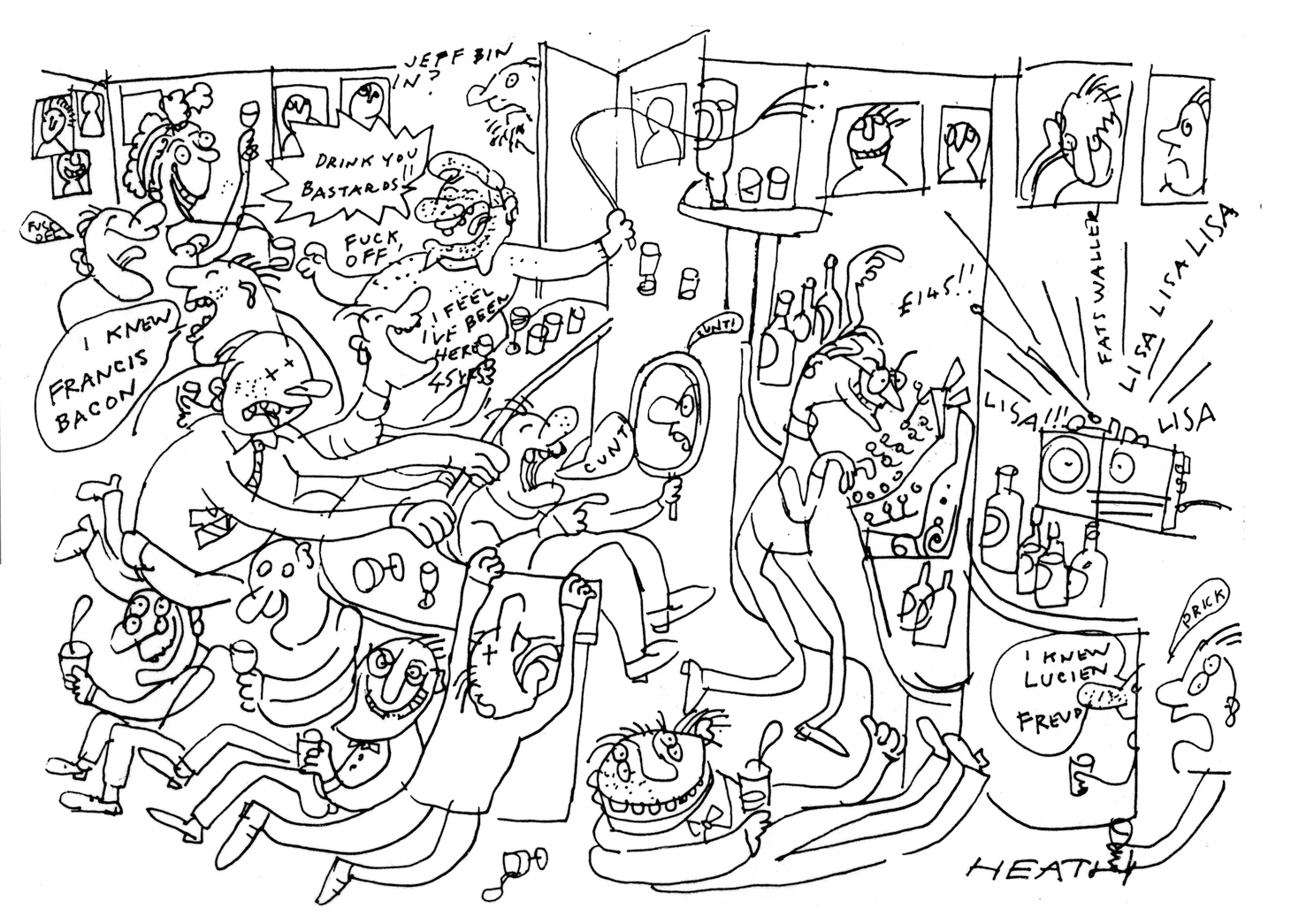

The Colony was an anarchic dictatorship run by Belcher and her successors Ian Board and Michael Wojas, both of whom transitioned from loyal barmen to Club proprietors. For sixty years, membership was contingent on wit, with prospective members expected to verbally spar with the staff. Most newcomers simply balked after being greeted as “fuckface” or “cunty” at the door. “If you told a joke you would be thrown out,” recalls David Edwards — a member and former publican. “You had to survive on your own anecdotes and wit — Muriel and Ian were very strict on that.”

In the book’s introduction, Coffield likens Belcher to Gertrude Stein. Both were lesbians, and composite “mentor, critic, and guru,” Coffield reasons, a comparison that jazz singer, George Melly, summarily rejects. “We embellish things with hindsight. If you’d gone up to Muriel Belcher and asked her if she’d started a club to help make the world a freer, more liberal place, she’d have said, ‘fuck off.’ I don’t think she knew one picture from another.” “But,” Melly concedes, “she did have a remarkable eye for painters, and a nose for writers. She could tell if someone had potential immediately and she would cultivate them.” Bacon was brought to the Colony by the poet Brian Howard on December 14, 1948 — the day before its official opening. “Muriel came over” Bacon recalls, “she thought I knew a lot of rich people [and] knew I didn’t have much money, so she said, ‘I’ll give you £10 a week and you can drink absolutely freely… don’t think of it as a salary. Just bring in people when you feel like it.’ I loved Muriel enormously.”

As a consequence of Bacon and Belcher’s influence, the Colony became the bar of choice among Britain’s great post-war painters, among them Lucian Freud, Michael Andrews, and Frank Auerbach. Membership rapidly broadened to include publishers, poets, and graphic designers, transforming the diminutive room into a fertile site of artistic exchange. It was there that John Deakin met many of his photographic subjects, the renowned designer Germano Facetti began collaborating with publisher David Archer, and Bacon determined to show his work in Moscow — eventually becoming the first Western artist to exhibit behind the Iron Curtain.

Himself an artist, Coffield began frequenting the club in the late eighties during the twilight years of Ian Board’s reign. As part of a group show I organized in 2012, I interviewed the artist about his interest in cult and periphery figures (full disclosure: I chipped in £40 towards the book’s crowdfunding campaign). “No one else is going to paint these people because there’s no money in it and they’re not considered to be ‘establishment’ or bankable,” the artist told me. “I paint people who I think should be painted and who should be in the National Portrait Gallery.”

That same ethos has guided Coffield’s Colony project, where he capitalizes on the broader appeal of figures such as Bacon to draw readers to lesser known talents. Examples include artist Sir Francis Rose (aka ‘Lord Chaos’), whom Stein championed before he squandered his fortune, and Gerald Wilde (‘the Mad Artist’), who was erroneously reported dead by the Daily Express (the paper’s correction read “I’M FEELING VERY WELL SAYS ‘DEAD MAN’”). Coffield keenly dispels years of accumulated mythology, noting the habit of drinkers to embellish their tales. Contrary to popular myth, Dylan Thomas never threw up on the Colony floor, nor was Myra Hindley — Britain’s most notorious murderess — a patron (though her psychiatrist was). However, the model and showgirl Christine Keeler really was a regular. “She would never talk about anything of any interest,” opines David Marrion. “Stephen Ward, the poor man who was accused of being her pimp, also came to the club. He took his own life when the [Profumo] scandal broke.”

Comic tales of verbal sparring and bumbling aristocrats are matched by accounts of tragic and ignominious declines. Eva Johansen, a copywriter and Colony favorite, self-immolated after passing out with a cigarette. Nina Hamnett, the bohemian muse of Augustus John and Amedeo Modigliani, whittled away her final years in the club as a penniless, incontinent drunk. “I stumbled over Hamnett, a famous beauty in the 1920s,” recalls author Sandy Fawkes. “Even at that age, I recognized there was nothing funny in an old woman lying in a pool of her own piss.”

The running of the club took a severe toll on all three proprietors. Belcher spent her final years bedridden and afflicted by dementia. Board, who had modeled in his youth, developed an extraordinarily bulbous nose as a consequence of his drinking (“it’s my trademark,” he reportedly told Coffield), and lived in squalor. The Colony’s lifestyle proved

too much for some. Molly Parkin, the painter infamous for her unfettered and progressive writing on sexual mores, abandoned her membership and joined Alcoholics Anonymous. “I didn’t realize what alcohol could do to a face,” she recalls.

The Colony’s three proprietors lend the book a natural tripartite structure. Unlike Belcher and Board, Wojas cuts a gentler, less mercurial figure, though his demise was no less tragic. During the nineties the Colony was rediscovered by a younger, media-savvy clientele, including the YBAs whom Wojas wooed with dedicated performance nights. The events revitalized the club and its finances, with Damien Hirst noting, not unreasonably, that the Colony had become a “mortuary” — a 1950’s relic buoyed by the Edwardian sensibility of its aged regulars. Tracey Emin and Sarah Lucas were among the milieu who posed as Colony Room patrons in John Maybury’s 1998 film Love is the Devil, a dramatization of Bacon’s relationship with George Dyer. Mythologized on film, the bar had now truly broken cover. In the words of James Moores, the Club became “pop-starry.” Olympus cameras sponsored performance nights, and musicians such as Lisa Stansfield, Ian Dury, and Joe Strummer began to frequent the Colony. The deluge of younger members created a generational divide that imperiled the club. Tabloid reports of drug use and the brazen flouting of the smoking ban drew the unwelcome ire of the local council. Worse, Wojas had become a heroin user and was suspected of subsidizing his habit with club earnings. Having witnessed Board’s demise, Wojas became increasingly reluctant to renegotiate the club’s lease with its recalcitrant landlord. The protracted fight to save the Colony from regeneration was split among sectarian lines, with older members horrified by Wojas’ conduct. Tragically, Wojas succumbed to cancer in June 2010, eighteen months after the Club shuttered.

That the Colony survived for as long as it did was miraculous given Soho’s rapid gentrification from the eighties onwards. By the turn of the century, most of the area’s family-run businesses, night clubs, and adult stores had been supplanted by sleek post-production houses and luxury apartments. By-gone remnants such as Bar Italia and Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club have had to festishize and market their histories in order to survive. Beyond its cast of characters, Soho’s Lost Bohemia is also portrait of London’s creative transformation, ruminating, convincingly, that the city’s cultural industries have become increasingly stultified amid the forces of financialization and gentrification. Young creatives might be drinking and smoking less, but they’re also contending with unaffordable living standards, scrambling for dwindling studio spaces, and debt-saddled by their degrees. Risqué spaces such as the Colony have become a costly victim of the art sector’s professionalization. “It used to be the case that you get your work done, then have a good old drink up in the afternoon,” muses author David Hayles. “Now you grab your baguette and espresso and take them back to your work desk.”

Tales from the Colony Room: Soho’s Lost Bohemia (2020), by Darren Coffield, is available now from Unbound.

Tales from the Colony Room: Art and Bohemia, an exhibition of works by the Club’s members, opens at the Dellasposa Gallery (2a Bathhurst Street, Paddington, London) on September 15.